Just returned from Haiti, where I was reporting on the ongoing cholera epidemic, including in the remote fishing village of Belle-Anse in the Sud-Est Department. To get there, we rode motorcycles, caught a ride on a packed minivan over the mountains and then chartered a 15-foot skiff with a periodically dysfunctional outboard engine. The story I found, of how cholera came to Belle-Anse and how it currently holds the village in its deadly thrall, was dramatic, absurd, and tragic all at once. I hope I can do it justice. I’ll be writing about it in my forthcoming book.

Category: Science and Politics (Page 1 of 4)

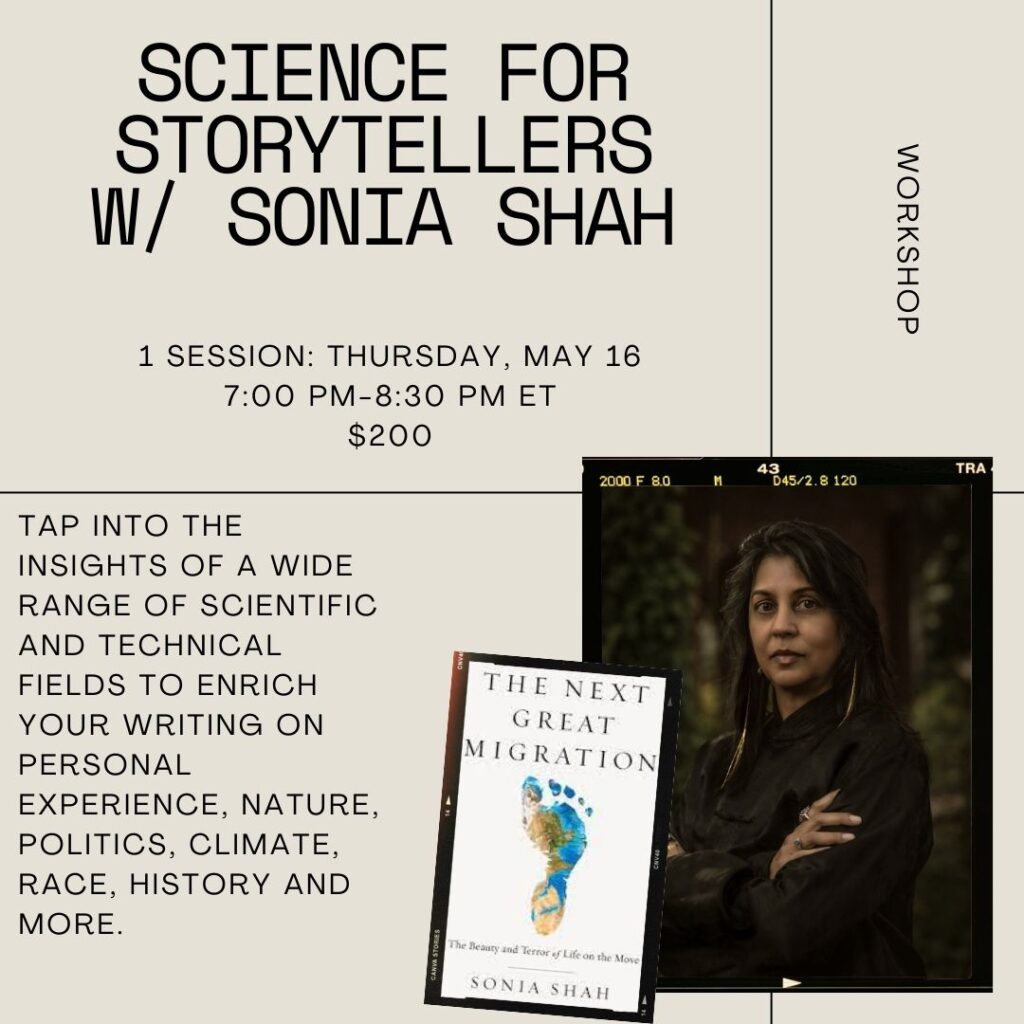

So happy to report that I’ve been selected to be the 2014 Ottaway Professor of Journalism at SUNY New Paltz! This is an endowed visiting professorship which I’ll be holding for the 2014 spring semester. There’ll be a few campus-wide lectures about my work and I’ll be teaching a small class on a topic of my choice, most likely something within the intersections of international politics, global health, and science journalism. Looking forward to it! As an added bonus, the lovely New Paltz campus is situated around the scenic Shawangunk mountains, a.k.a. the infamous Gunks for you rock climbing types. I may have to unearth my climbing shoes.

An important new report from the Amsterdam-based NGO Wemos describes how major multinational drug companies are continuing conduct unethical experiments on vulnerable populations including children and the mentally ill in South Africa and other developing countries, putting both their health and their human rights at risk.

I reported on unethical trials like these in South Africa for my book The Body Hunters. The drug industry’s stampede into developing countries like South Africa to conduct their experiments continues. With a high degree of inequality in many of these countries, there’s a great medical infrastructure in place to cater to the rich, and plenty of poor people upon which to wield it to conduct experiments. The experiments they conduct there often have little to do with the public health priorities of the local communities, mind you. Rather, the trials–which, as Wemos ably shows, endanger the health of enrolled subjects–are aimed at generating data to extend patents on drugs or market new ones in the major US and European markets. It’s the very definition of exploitation.

It’s not easy to report on these trials. Untangling the science, the ethics, and the regulatory hurdles is tricky, and it’s all too easy to sensationalize. Wemos gets it right. It’s a great report. Check it out here.

I spent a few weeks last winter in New Delhi, thanks to a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, learning about the spread of a gene called “NDM-1,” which can slip and slide into various species of bacteria, endowing them with the ability to resist all manner of antibiotics, including the last-resort IV antibiotics used exclusively in hospitals. NDM-1, which has been found in puddles and streams around Delhi, has been travelling the world in the bodies of patients who fly into the city for cheap surgeries at local hospitals, a trend supported by the Indian government as a lucrative new source of revenue. I wrote about different aspects of the problem for The Atlantic and Foreign Affairs (and created this audio slide show that’s hosted on the Pulitzer Center’s website): next month, a longer, more narrative piece arrives in Le Monde Diplomatique.

An alarming new report published by The Lancet on April 5 reveals that drug-resistant malaria has spontaneously emerged from yet another hotspot in southeast Asia. If the super-parasites erupt elsewhere—such as in malaria’s African heartland—years of progress against the disease could be rapidly unravelled.

Malaria parasites that resist the wonder drug, artemisinin, were first sighted five years ago, in western Cambodia. Alarmed public health officials sprang into action, with stepped up containment efforts to prevent the bug from spreading. But all that may have been for naught, as a team of international researchers now report that similarly impervious malaria parasites had already emerged along the Thai-Myanmar border, some 800 kilometers away. Evidence suggests that they did not spread there from Cambodia but rather arose spontaneously, eight or more years ago.

Containment, in other words, is no longer possible. For the millions whose lives have been saved by artemisinin drugs, this is worrying news indeed. It’s possible that these impervious parasites could erupt almost anywhere artemisinin drugs are used. Perhaps they already have.

Ironically, artemisinin drugs saved the world from an earlier drug-resistant malaria. Launched after World War II, chloroquine was for decades the world’s wonder drug for malaria, popped like aspirin across the tropics. Widely available for pennies without a prescription, people consumed it with abandon. Chloroquine-resistant malaria first emerged in 1957, and within a few decades had spread from Southeast Asia across the globe. With no drug in sight to take its place, malaria deaths skyrocketed, tripling over the course of the 1980s and 1990s.

Artemisinin drugs capable of taming chloroquine-resistant malaria became widely available only after 2004, when international donors and the World Health Organization started to promote their distribution. International drug programs such as the Affordable Medicines Facility for Malaria, the brain child of the Nobel-prize-winning economist Kenneth Arrow, aimed to blanket the malarious world with artemisinin drugs, providing massive subsidies so that these meds—like chloroquine—would become widely available, without a prescription, for pennies. It worked. By 2010, global production of artemisinin drugs had increased to 130.6 million doses, from just 11.2 million in 2005. The distribution of these drugs coincided with scaled-up prevention efforts, in which insecticides were impregnated into hundreds of millions of bednets and sprayed on the interior walls of scores of homes, to kill and repel malarial mosquitoes.

Now the gains of that chemical blitz—a 31 percent drop in global malaria mortality between 2005 and 2010— are under siege. Along with drug-resistant parasites erupting in southeast Asia, malarial mosquitoes resistant to antimalarial insecticides have spread across central and western Africa.

Elsewhere, other infectious diseases are similarly routing our killing chemicals. In recent years, bacteria capable of defanging our most powerful antibiotic drugs have emerged and spread, such as the notorious NDM-1 or “New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1,” which can resist 14 kinds of antibiotics, including the last-resort drugs used solely in hospitals, and which has so far spread to over 35 countries. Extensively drug-resistant, or “XDR” tuberculosis, plagues at least 58 countries, and in January, India became the third country after Iran and Italy to fall victim to totally drug resistant or “TDR” tuberculosis, an untreatable form of the disease.

Call it the revenge of the microbes. The more poison we throw at them, the faster they learn to circumvent our chemicals. That reality is also why the tools required to continue fighting this war are becoming increasingly scarce. Experts expect it will be at least 8 years before a new drug to treat drug-resistant malaria makes it to market. There hasn’t been a new drug launched to treat tuberculosis in nearly 50 years. There are currently no drugs in development that will treat NDM-1 bacterial infections. Why? Because these drugs are expensive to develop, and yet, the more people buy them, the faster the drug becomes obsolete and un-sellable. As a result, very few drug companies spend much time or money developing anti-microbial drugs anymore. It’s bad for business.

The sad truth is that each wonder drug we’ve thrown at malaria—and every other infectious disease—has fallen to drug-resistant pathogens. Artemisinin drugs, it seems, may be next. But the next generation of wonder drugs doesn’t have to suffer the same fate.

Microbiologists and others are developing new approaches to drugs and insecticides that minimize the emergence of drug-resistance, by targeting only the worst, most disease-causing aspects of pathogens. In malaria, for example, Penn State biologist Andrew Read has proposed the development of insecticides that leave intact young, reproducing mosquitoes and target only the oldest mosquitoes that are most likely to transmit malaria. That way, insecticide-resistant mosquitoes have zero advantage over susceptible ones. Insecticides and drugs developed using this logic could be virtually “evolution proof.”

Similarly, scientists are developing new rapid diagnostic tests that can ensure that bug-fighting drugs are used exclusively on active, disease-causing infections, greatly reducing opportunities for drug-resistant bugs to spread. New drug-resistance surveillance networks can now use molecular techniques to pinpoint the earliest signs of resistance, so that drug regimens can be changed before they fail. Disease-prevention methods that don’t rely on killing chemicals at all, such as improved housing and environmental management for malaria, and better hospital hygiene in hospitals and communities for drug-resistant bacteria, can help ward off infection without encouraging drug-resistant microbes at all.

Slowing the spread of drug-resistant malaria will take time and resources. But it’s better than the alternative: the loss of yet another wonder drug and a new era of unstoppable infections.

The Hunger Games, courtesy of Lionsgate

The World Food Program, among other anti-hunger groups, have teamed up with the film “The Hunger Games” to raise awareness about hunger (the real kind as opposed to the fictional, game-like version). Here’s my review of their efforts–and the film–from The Lancet.

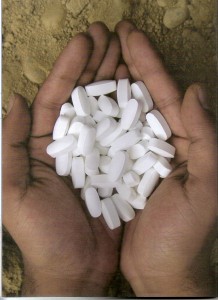

Photo by Sonia Shah

This is the first of a series of reports on NDM-1 bacteria, bugs endowed with the ability to resist not only commonly used antibiotics but the last-resort IV antibiotics used only in hospitals. NDM-1 first emerged in New Delhi (and is, controversially, named after the city) and has since spread to over 35 countries, primarily in the bodies of medical tourists. I recently returned from a trip to New Delhi, and filed this report for The Atlantic and the Pulitizer Center on Crisis Reporting, which funded my trip. Photos, video, an audio slideshow, and more stories in Foreign Affairs and Le Monde Diplomatique are forthcoming. Stay tuned.

I’ll be talking about my article on private interests in global health on NPR’s “To The Point” today, live at 11 am PT, 2 pm ET. Economist Daniel Altman and Center for Science in the Public Interest’s Bill Jeffrey will be joining, too. Check here for a station list or to listen now.